Windrush generation: Who are they and why are they facing problems?

18 April 2018, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43782241

18 April 2018, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43782241

Replies sorted oldest to newest

18 April 2018, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43782241

Prime Minister Theresa May has apologised to Caribbean leaders over deportation threats made to the children of Commonwealth citizens, who despite living and working in the UK for decades, have been told they are living here illegally because of a lack of official paperwork.

Those arriving in the UK between 1948 and 1971 from Caribbean countries have been labelled the Windrush generation.

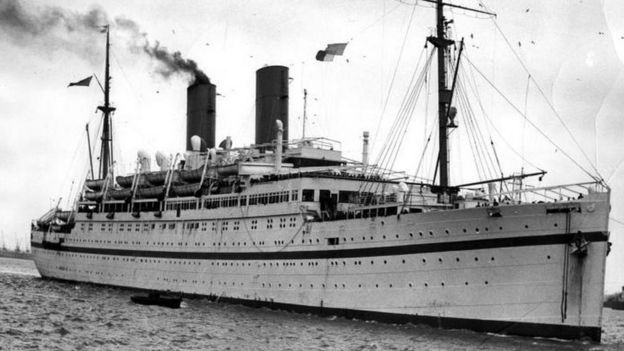

This is a reference to the ship MV Empire Windrush, which arrived at Tilbury Docks, Essex, on 22 June 1948, bringing workers from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and other islands, as a response to post-war labour shortages in the UK.

The ship carried 492 passengers - many of them children.

It is unclear how many people belong to the Windrush generation, since many of those who arrived as children travelled on parents' passports and never applied for travel documents - but they are thought to be in their thousands.

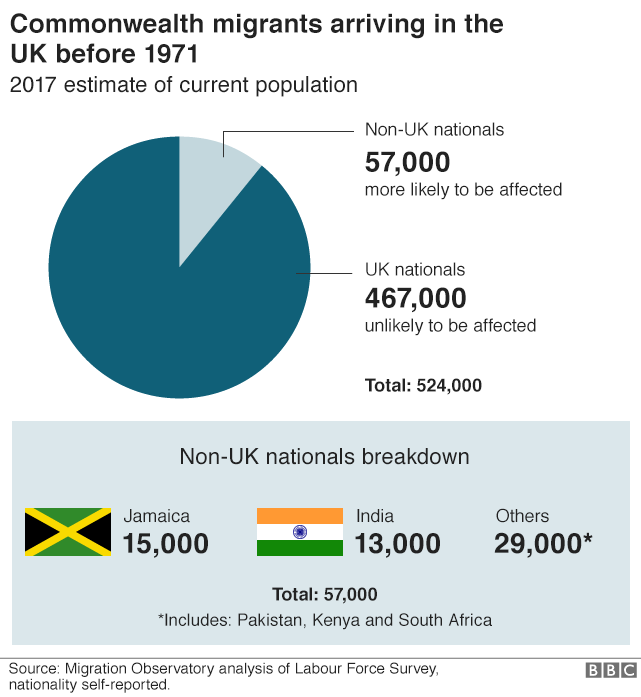

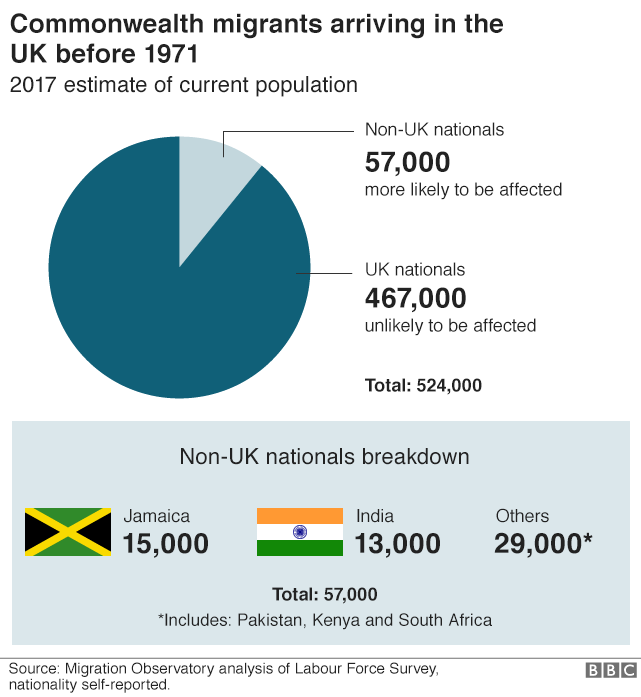

There are now 500,000 people resident in the UK who were born in a Commonwealth country and arrived before 1971 - including the Windrush arrivals - according to estimates by Oxford University's Migration Observatory.

The influx ended with the 1971 Immigration Act, when Commonwealth citizens already living in the UK were given indefinite leave to remain.

After this, a British passport-holder born overseas could only settle in the UK if they firstly had a work permit and, secondly, could prove that a parent or grandparent had been born in the UK.

Many of the arrivals became manual workers, cleaners, drivers and nurses - and some broke new ground in representing black Britons in society.

The Jamaican-British campaigner Sam Beaver King, who died in 2016 aged 90, arrived at Tilbury Docks in his 20s before finding work as a postman.

He later became the first black Mayor of Southwark in London.

The Labour MP David Lammy, whose parents arrived in the UK from Guyana, describes himself as a "proud son of the Windrush".

I am campaigning for an amnesty but in reality it would not be an amnesty because that word implies wrongdoing. These people have done nothing wrong. Govt must simply do the right thing, establish a humane route to clarifying their status in this country & change burden of proof.

The Home Office did not keep a record of those granted leave to remain or issue any paperwork confirming it - meaning it is difficult for Windrush arrivals to prove they are in the UK legally.

And in 2010, landing cards belonging to Windrush migrants were destroyed by the Home Office.

Because they came from British colonies that had not achieved independence, they believed they were British citizens.

International Development Secretary Penny Mordaunt said there was "absolutely no question" of the Windrush generation's right to remain.

She told BBC Radio 4's Today programme: "People should not be concerned about this - they have the right to stay and we should be reassuring them of that."

Mrs May's spokesman said the prime minister was clear that "no-one with the right to be here will be made to leave".

Those who lack documents are now being told they need evidence to continue working, get treatment from the NHS - or even to remain in the UK.

Changes to immigration law in 2012, which require people to have documentation to work, rent a property or access benefits, including healthcare, have left people fearful about their status.

The BBC has learned of a number of cases where people have been affected.

Sonia Williams, who came to the UK from Barbados in 1975, aged 13, said she had her driving licence withdrawn and lost her job when she was told she did not have indefinite leave to remain.

Sonia Williams came to the UK in the 1970s

Sonia Williams came to the UK in the 1970s

"I came here as a minor to join my mum, dad, sister and brother," she told BBC Two's Newsnight. "I wasn't just coming on holiday."

Paulette Wilson, 61, who came to Britain from Jamaica aged 10 in the late 1960s, said she received a letter saying she was in the country illegally.

"I just didn't understand it and I kept it away from my daughter for about two weeks, walking around in a daze thinking 'why am I illegal?'"

In her apology, Mrs May insisted the government was not "clamping down" on Commonwealth citizens, particularly those from the Caribbean.

The government is creating a task force to help applicants demonstrate they are entitled to work in the UK. It aims to resolve cases within two weeks of evidence being provided.

Announcing the move, Home Secretary Amber Rudd apologised for the "appalling" way the Windrush generation had been treated.

She told MPs the Home Office had "become too concerned with policy and strategy - and loses sight of the individual".

Delegates at this week's Commonwealth heads of government meeting in London are to discuss the situation.

Not everybody who arrived in the UK during the period faced such problems.

Not everybody who arrived in the UK during the period faced such problems.

Children's TV presenter Floella Benjamin, who was born in Trinidad, said: "I could so easily be one of the Windrush children who are now asked to leave but I came to Britain as a child without my parents on a British passport."

Baroness Benjamin, 68, moved to Beckenham, Kent, in 1960.

"Before 1973 many Caribbean kids came to Britain on their parents' passport and not their own. That's why many of these cases are coming to light," she said.

More than 160,000 people have signed a petition calling on the government to grant an amnesty to anyone who arrived in the UK as a minor between 1948 and 1971.

Its creator, the activist Patrick Vernon, calls on the government to stop all deportations, change the burden of proof, and provide compensation for "loss and hurt".

Mr Vernon, whose parents migrated to the UK from Jamaica in the 1950s, called for "justice for tens of thousands of individuals who have worked hard, paid their taxes and raised children and grandchildren and who see Britain as their home."

However, some people have objected to the word "amnesty" - saying it implies the Windrush generation were not legally entitled to live in the UK in the first place.

The Windrush was recreated during the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games

The Windrush was recreated during the opening ceremony of the London 2012 Olympic Games

Events are held annually to commemorate the Windrush's arrival 70 years ago, and the subsequent wave of immigration from Caribbean countries.

A model of the ship featured in the opening ceremony for the London 2012 Olympic Games, while the lead-up to Windrush Day on 22 June is being marked with exhibitions, church services and cultural events.

They include works by photographer Harry Jacobs, who took portraits of Caribbean families coming to London in the 1950s, which are being exhibited in Brixton, south-east London.

[[Quote from the article]]

The Home Office and British government were further accused of having known about the negative impacts that the 'hostile environment poicy' was having on Windrush immigrants since as early as 2013, and of having done nothing to remedy them.[57][58]

Those highlighting the issue included, journalists Amelia Gentleman[59] and Gary Younge,[19] Caribbean diplomats Kevin Isaac[37], Seth George Ramocan,[47] and Guy Hewitt,[44][47] British parliamentarians Herman Ouseley[7] and David Lammy MP.[60] [61] Amelia Gentleman, of The Guardian was later awarded the 2018 Paul Foot Award for her coverage of, what the judges described as: "the catastrophic consequences for a group of elderly Commonwealth-born citizens who were told they were illegal immigrants, despite having lived in the UK for around 50 years".[59][62]

======================

The scandal drew attention to other issues relating to UK migration policy and practice, including treatment of other migrants,[104][105][106] and of asylum seekers and what the status of EU nationals living in Britain would be after Brexit.[93][27][67]

Stephen Hale of Refugee Action, said, “All of the things those [Windrush] people have been through are also experiences that people are going through as result of asylum system.[107] Some skilled workers had been threatened with deportation after living and working in the UK for over a decade because of minor irregularities in their tax returns, some were allowed to stay and fight deportation but prevented from working and denied access to the NHS while doing so. Sometimes the irregularities were due to the tax authorities not the migrant.[108]

In an interview with BBC's Andrew Marr on 3 June, Sajid Javid said that key parts of the UK's immigration policy would be reviewed and that changes had already been made to the "hostile environment" approach to illegal immigration in the wake of the Windrush scandal.[109]

Following complaints by ministers, the Home Office is reported to have set up an inquiry to investigate where the leaked documents that led to Rudd's departure came from.[110][111][112]

[[Unquote from the article]]

The Windrush scandal is a 2018 British political scandal concerning people who were wrongly detained, denied legal rights, threatened with deportation, and, in around 63 cases,[1] wrongly deported from the UK by the Home Office. Many of those affected had been born British subjects and had arrived in the UK before 1973, particularly from Caribbean countries as members of the Windrush generation.[2]

As well as those who were wrongly deported, an unknown number were wrongly detained, lost their jobs or homes, or were denied benefits or medical care to which they were entitled.[1] A number of long-term UK residents were wrongly refused re-entry to the UK, and a larger number were threatened with immediate deportation by the Home Office.

Linked by commentators to the "hostile environment policy" instituted by Theresa May during her time as Home Secretary,[3][4][5] the scandal led to the resignation of Amber Rudd as Home Secretary in April 2018, and the appointment of Sajid Javid as her successor.[6] The scandal also prompted a wider debate about British immigration policy and Home Office practice.

The scandal came to public attention as a result of a campaign mounted by Caribbean diplomats to the UK, British parliamentarians and charities, and an extended series of articles in The Guardian newspaper.[7]

The British Nationality Act 1948 gave citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies status, and the right to settle in the UK,[8] to everyone who was at that time a British subject by virtue of having been born in a British colony. The act, and encouragement from British Government campaigns in Caribbean countries, led to a wave of immigration from the Caribbean. Between 1948 and 1970 nearly half a million people moved from the Caribbean to Britain, which in 1948 faced severe labour shortages in the wake of the Second World War. These immigrants were later referred to as "the Windrush generation".[2] In addition to working age adults, many children travelled from the Caribbean to join parents or grandparents in the UK, or travelled with their parents, without their own passports.[9]

Since these people had a legal right to come to the UK, they neither needed nor were given any documents upon entry to the UK, nor following changes in immigration laws in the early 1970s.[10] Many worked – or attended schools in the UK, without any official documentary record of their having done so, other than the same records as any UK-born citizen.[11]

Many of the countries from which the immigrants had come, became independent of the UK after 1948, and therefore people then living there became citizens of those countries. Additionally, a series of legislative measures in the 1960s and early 1970s limited the rights of citizens of these former colonies, now members of the Commonwealth, to come to, or work in the UK. However, anyone who had arrived in the UK from a Commonwealth country before 1973 was granted an automatic right to permanently remain,[10] unless they left the UK for more than two years.[2] Since the right was automatic, many people in this category were never given, or asked to provide, documentary evidence of their right to remain either at that time, or in the following four decades,[11] during which many continued to live and work in the UK, believing themselves to be British.[2]

A clause in the 1999 Immigration Act specifically protected longstanding residents of the UK from Commonwealth countries from enforced removal. The clause was not transferred to 2014 immigration legislation. The clause was removed as Commonwealth citizens living in the UK before 1 January 1973 were "adequately protected from removal", according to a Home Office spokesperson.[12]

The hostile environment policy, which came into effect in October 2010,[13] is a set of administrative and legislative measures designed to make staying in the United Kingdom as difficult as possible for people without "leave to remain", in the hope that they may "voluntarily leave".[14][15][16] In 2012, the then Home Secretary Theresa May stated that "The aim is to create, here in Britain, a really hostile environment for illegal immigrants".[14] The policy was widely seen as being part of a strategy of reducing UK immigration figures to the levels promised in the 2010 Conservative Party Election Manifesto.[14][17][18] Measures introduced as parts of the policy include a legal requirement for landlords, employers, the NHS, charities, community interest companies and banks to carry out ID checks, and to refuse sevices if the individual is unable to prove legal residence in the UK.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] Landlords, employers and others are liable to fines of up to £10,000[3] if they fail to comply with these measures[27]

The policy also implemented a more complicated application process to get 'leave to remain' and encouraged voluntary deportation.[28][29] The policy coincided with sharp increases in Home Office fees for processing "leave to remain", naturalisation and registration of citizenship applications.[30][31] The BBC reported that the Home Office had made a profit of more than £800m from nationality services between 2011 and 2017.[31]

The term 'hostile environment', had first been used under the last Labour Government.[32] On 25 April 2018, in answer to questions in Parliament during the Windrush scandal, Theresa May, now British Prime Minister, said that the hostile environment policy would remain government policy.[33]

The Home Office received warnings from 2013 onwards that many Windrush generation residents were being treated as illegal immigrants and that older Caribbean born people were being targetted. The Refugee and Migrant Centre in Wolverhampton said their caseworkers were seeing hundreds of people receiving Capita letters telling them that they had no right to be in the UK, some of whom were told to arrange to leave the UK at once. Roughly half the letters went to people who already had leave to remain, or were in the process of regularising their immigration status. Caseworkers had warned the Home Office directly and also through local MPs of these cases since 2013. People considered illegal were sometimes losing their jobs[19] or homes as a consequence of having benefits cut off, and some had been refused medical care under the NHS,[34][35] some placed in detention centres as preparation for their deportation, some deported or refused right to return to the UK from abroad.[36][37]

In 2013 Caribbean leaders had put the deportations on the agenda at the Commonwealth meeting in Sri Lanka[38][37] and in April 2016 Caribbean governments told the then Foreign Secretary that immigrants who had spent most of their lives in the UK were facing deportation and their concerns were passed on at the time to the Home Office.[39][37] Shortly before the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in April 2018, 12 Caribbean countries made a formal request for a meeting with the British Prime Minister to discuss the issue, which was rejected by Downing Street,[40]

In January 2018, the Home Affairs Select Committee issued a report which said the hostile environment policies were “unclear” and had seen too many people threatened with deportation based on “inaccurate and untested” information. The report warned that the errors being made – in one instance 10% – threatened to undermine the "credibility of the system". A major concern voiced in the report was that the Home Office did not have any system to evaluate the effectiveness of its hostile environment provisions, and commented that there had been a “failure” to understand the effects of the policy. The report also noted that a shortage of accurate data about the scale of illegal immigration had allowed public anxiety about the issue to “grow unchecked”, which, the report said, showed government “indifference” towards an issue of “high public interest”. [27]

A month before the report was published, more than 60 MPs, academics and campaign groups wrote an open letter to Amber Rudd urging the Government to halt the “inhumane” policy, citing the Home Office's “poor track record” of dealing with complaints and appeals in a timely manner.[27]

From November 2017,[41] newspapers reported that the British government had threatened to deport people from Commonwealth territories who had arrived in the UK before 1973 if they could not prove their right to remain in the UK.[10] Although primarily identified as the Windrush generation and mainly from the Caribbean,[9] it was estimated in April 2018 that, based on figures provided by the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford,[42] that up to 57,000 Commonwealth migrants could be affected, of whom 15,000 were from Jamaica alone.[43] In addition to those from the Caribbean, cases of people affected who had been born in Kenya, Cyprus, Canada,[44][45] and Sierra Leone were identified in the press.[46]

The press coverage accused Home Office agencies of operating a "guilty until proven innocent"[47] and "deport first, appeal later" regime;[48] of targetting the weakest groups, particularly those from the Caribbean;[48][49] of inhumanely applying regulations by cutting off access to jobs, services,[50] medical treatment,[51][3] and bank accounts while cases were still being investigated; of losing large numbers of original documents which proved right to remain;[52][27] of making unreasonable demands for documentary proof [53][50][54] – in some instances, elderly people had been asked for 4 documents for each year they had lived in the UK,[19][48] and of leaving people stranded outside the UK because of British administrative errors or intransigence.[55][56][50][57][3] Other cases covered in the press, involved adults born in the UK, whose parents were 'Windrush' immigrants and who had been threatened with deportation and had their rights removed, because they were unable to prove that their parents were legally in the UK at the time of their birth.[citation needed]

The Home Office and British government were further accused of having known about the negative impacts that the 'hostile environment poicy' was having on Windrush immigrants since as early as 2013, and of having done nothing to remedy them.[57][58]

Those highlighting the issue included, journalists Amelia Gentleman[59] and Gary Younge,[19] Caribbean diplomats Kevin Isaac[37], Seth George Ramocan,[47] and Guy Hewitt,[44][47] British parliamentarians Herman Ouseley[7] and David Lammy MP.[60] [61] Amelia Gentleman, of The Guardian was later awarded the 2018 Paul Foot Award for her coverage of, what the judges described as: "the catastrophic consequences for a group of elderly Commonwealth-born citizens who were told they were illegal immigrants, despite having lived in the UK for around 50 years".[59][62]

In early March 2018, questions began to be asked in Parliament about individual cases that had been highlighted in the press. On 14 March, Opposition Leader Jeremy Corbyn asked May about an individual who had been refused medical treatment under the NHS during Prime Minister's Questions in the House of Commons, May initially said she was "unaware of the case", but later agreed to "look into it".[63] Parliament thereafter continued to be involved in what was increasingly being referred to as "the Windrush scandal".

On 16 April 2018 David Lammy MP challenged Amber Rudd in the House of Commons to give numbers as to how many had lost their jobs or homes, been denied medical care, or been detained or deported wrongly. Lammy called on Rudd to apologise for the threats of deportation and called it a "day of national shame", blaming the problems on the government's "hostile environment policy".[60] Rudd replied that she did not know of any, but would attempt to verify that.[citation needed] In late April, Rudd faced increasing calls for her to resign and for the Government to abandon the "hostile environment policy".[64][65] There were also calls for the Home Office to reduce fees for immigration services.[30][31]

On 2 May 2018, the opposition Labour Party introduced a motion in the House of Commons seeking to force the government to release documents to the Home Affais Select Committee, concerning its handling of cases involving people who came to the UK from Commonwealth countries between 1948 and the 1970s, the motion was defeated by 316 votes to 221.[9]

On 25 April, in answer to a question put to her by the Home Affairs Select Committee about (numerical) deportation targets, Rudd said she was unaware of such targets,[66] saying “that’s not how we operate”,[67] although another witness had discussed deportation targets.[68] The following day, Rudd admitted in Parliament that targets had existed, but characterised them as "local targets for internal performance management" only, not "specific removal targets". She also claimed that she had been unaware of them and promised that they would be scrapped.[69][61]

Two days later, The Guardian published a leaked memo, which had been copied to Rudd's office, the memo said that the department had set "a target of achieving 12,800 enforced returns in 2017–18'" and "we have exceeded our target of assisted returns". The memo added that progress had been made towards "the 10% increased performance on enforced returns, which we promised the Home Secretary earlier this year". Rudd responded by saying she had never seen the leaked memo, “although it was copied to my office, as many documents are”.[70][71]

The New Statesman said that the leaked memo gave, "in specific detail the targets set by the Home Office for the number of people to be removed from the United Kingdom. It suggests that Rudd misled MPs on at least one occasion".[72][73] Diane Abbott MP called for Rudd's resignation: "Amber Rudd either failed to read this memo and has no clear understanding of the policies in her own department, or she has misled Parliament and the British people."[74] Abbott also said, "The danger is that (the) very broad target put pressure on Home Office officials to bundle Jamaican grandmothers into detention centres".[75]

On 29 April 2018, The Guardian published a private letter [76] from Rudd to Thesesa May dated January 2017 in which Rudd wrote of an "ambitious but deliverable" target for an increase in the enforced deportation of immigrants. Later that day, Rudd resigned as Home Secretary.[77][78]

On 29 April 2018, Rudd resigned as Home Secretary,[77][78] saying in her resignation letter that she had "inadvertently misled the Home Affairs Select Committee [...] on the issue of illegal immigration".[79] Later that day Sajid Javid was named as her successor.[80]

Shortly before, Javid, while still Communities Secretary, had said in a Sunday Telegraph interview "I was really concerned when I first started hearing and reading about some of the issues ... My parents came to this country ... just like the Windrush generation ... When I heard about the Windrush issue I thought, 'That could be my mum, it could be my dad, it could be my uncle... it could be me.'"[81][82]

On 30 April, Javid made his first appearance before Parliament as Home Secretary. He promised legislation to ensure the rights of those affected, and said that the government would "do right by the Windrush generation".[83] In comments seen by the press as distancing himself from Theresa May, Javid told Parliament that "I don’t like the phrase hostile [...] I think it is a phrase that is unhelpful and it doesn’t represent our values as a country".[84][85]

On 15 May 2018, Javid told the Home Affairs Select Committee that 63 people had thus far been identified as having been possibly wrongly deported though stating the figure was provisional and could rise. He also said that he had been unable to establish at that point how many Windrush cases had been wrongfully detained,[86]

By late May 2018 the government had contacted 3 out of the 63 people possibly wrongly deported,[87] and on 8 June, Seth George Ramocan, the Jamaican high commissioner in London said he had still not received either the numbers or the names of those people the Home Office believed they had wrongly deported to Jamaica, so that Jamaican records could be checked for contact details.[56] By late June, long delays were being reported in processing "leave to remain" applications due to the large numbers of people contacting the Home Office. The Windrush hotline had recorded 19,000 calls up to that time, 6,800 of which were identified as potential Windrush cases. 1,600 people had by then been issued documentation after having appointments with the Home Office.[56]

On 29 June the Parliamentary Human Rights Select committee published a "damning" report on the exercise of powers by immigration officials. MPs and Peers concluded in the report that there had been "systemic failures" and rejected the Home Office description of a "a series of mistakes" as not "credible of sufficient". The report concluded that the Home Office demonstrated a "wholly incorrect approach to case-handling and to depriving people of their liberty", and urged the Home Secretary to take action against the "human rights violations" occurring in his department. The committee had examined the cases of two people who had both twice been detained by the Home Office, whose detentions the report described as "simply unlawful" and whose treatment was described as "shocking". The committee sought to examine 60 other cases.[54][88][89]

Harriet Harman MP, and chair of the committee accused immigration officials of being "out of control", and the Home Office of being a "law unto itself". Harman commented that "protections and safeguards have been whittled away until what we can see now ... [is] that the Home Office is all powerful and human rights have been totally extinguished." Adding that " even when they're getting it wrong and even when all the evidence is there on their own files showing that they have no right to lock these people up, they go ahead and do it."[88][90]

On 3 July the Home Affairs Select Committee (HASC) published a critical report which said that unless the Home Office was overhauled, the scandal would "happen again, for another group of people”. The report found that "a change in culture in the Home Office over recent years", had led to an environment in which applicants had been "forced to follow processes that appear designed to set them up to fail”. The report questioned whether the hostile environment should continue in its current form, commenting that “rebranding it as the ‘compliant’ environment is a meaningless response to genuine concerns”,[1][91] (Sajid Javid had previously referred to the policy as the ‘compliant' environment policy).[92]

The report recommended that the Home Office should re-assess all hostile environment policies to evaluate their "“efficacy, fairness, impact (both intended and unintended consequences) and value for money”, as the policy placed "a huge administrative burden and cost on many parts of society, without any clear evidence of its effectiveness but with numerous examples of mistakes made and significant distress caused".[93]

The report made a series of recommendations, designed to give the "Home Office a more human face”. It also called for "passport fees to be abolished for Windrush citizens; for a return to face-to-face immigration interviews; for immigration appeal rights and legal aid to be reinstated; and for the net migration target to be dropped".[1]

The report commented that they had hoped to uncover the extent of the impact on the Windrush generation but that the government had "not been able to answer many of our questions … and we have not had access to internal Home Office papers”. Commenting that it was "unacceptable that the Home Office still cannot tell us the number of people who have been unlawfully detained, were told to report to Home Office centres, who lost their jobs, or were denied medical treatment or other services.”[1]

The report also recommended extending the government compensation scheme to recognise "emotional distress as well as financial harm" and that the scheme should be open to Windrush children and grandchildren who had been adversely affected. The report reiterated its call for an immediate hardship fund for those in acute financial difficulty.[1][91] Committee chair Yvette Cooper said the decision to delay hardship payments was "very troubling" and victims "should not have to struggle with debts while they are waiting for the compensation scheme".[91]

The report also said that Home Office officials should have been aware of, and addressed, the problem much earlier,[94] cross-party MPs on the committee noted that the Home Office had taken no action during the months in which the issue had been highlighted in the press.[93]

The Labour party responded to the report by saying "many questions remained unanswered by the Home Office". Shadow Home Secretary Diane Abbott said it was a “disgrace” that the government had not yet published "a clear plan for compensation" for Windrush cases and that it had refused to institute a hardship fund, "even for people who have been made homeless or unemployed by their policies”.[1][91][95]

In response to questions from Parliamentary select committees, and questions asked in Parliament, the Home Office issued a number of replies during the scandal.

On 28 June a letter to the HASC from the Home Office reported that, it had "mistakenly detained" 850 people in the five years between 2012 and 2017. In the same five year period, the Home Office had paid compensation of over £21m for wrongful detention. Compensation payments varied between £1 and £120,000, an unknown number of these detentions were Windrush cases. The letter also acknowledged that 23% of staff working within immigration enforcement had received performance bonuses, some staff had been set “personal objectives” “linked to targets to achieve enforced removals” on which bonus payments were made.[67]

Figures released on 5 June by immigration minister Caroline Nokes revealed that in the 12 months prior to March 2018, 991 seats had been booked on commercial flights by the Home Office to remove people to the Caribbean who were suspected of being in the UK illegally. The 991 figure was not necessarily the number of deportations as some removals may not have happened, and others may have involved multiple tickets for one person’s flights. The figures did not say how many of the tickets booked were used for deportations. Nokes also said that in the two-year period from 2015 to 2017, the government had spent £52m on all deportation flights, including £17.7m on charter flights. Costs for the 12 months prior to March 2018 were not available.[96]

Amber Rudd, while still Home Secretary, apologised for the "appalling" treatment of the Windrush generation.[97] On 23 April 2018, Rudd announced that compensation would be given to those affected and, in future, fees and language tests for citizenship applicants would be waived for this group.[65] Theresa May also apologised for the "anxiety caused" at a meeting with 12 Caribbean leaders, though she was unable to tell them "definitively" whether anyone had been wrongly deported.[98] May also promised that those affected would no longer need to rely on providing formal documents to prove their history of residency in the UK, nor would they incur costs in getting necessary papers.[99]

On 24 May Sajid Javid, the new Home Secretary, outlined a series of measures to process citizenship applications for people affected by the scandal. The measures included free citizenship applications for children who joined their parents in the UK when they were under 18, also for children born in the UK of Windrush parents and free confirmation of right to remain for those entitled to it, but currently outside the UK, subject to normal good character requirements. The measures were criticised by MPs, as they provided no right of appeal or review of decisions. Yvette Cooper, chair of the Commons Home Affairs Committee, said, “Given the history of this, how can anyone trust Home Office not to make further mistakes? If the Home Secretary is confident that senior caseworkers will be making good decisions in Windrush cases, he has nothing to fear about appeals and reviews.” Javid also said that a Home Office team had identified 500 potential cases thus far.[100]

In subsequent weeks Javid also promised to provide figures on how many people had been wrongly detained and indicated that he did not believe in quantified targets for removals.[67]

On 21 May 2018, it was reported that many Windrush victims were still destitute, sleeping rough or on the sofas of friends and relatives while waiting for Home Office action. Many could not afford to travel to Home Office appointments if they got them. David Lammy MP described it as, “yet another failure in a litany of abject failures that Windrush citizens are being left homeless and hungry on the streets.”[101] In late May and early June, there were calls from MP's for a hardship fund to be set up to meet urgent needs.[101][102] By late June, it was reported that the government’s two-week deadline for resolving cases has been repeatedly breached, and that many of the most serious cases still had not been addressed. Jamaican High Commissioner Seth George Ramocan said: “There has been an effort to correct the situation now that it has become so very open and public.” [56]

The only official record of the arrival of many "Windrush" immigrants in the 1950s through to the early 1970s were landing cards collected as they disembarked from ships in UK ports. In subsequent decades these cards were routinely used by British immigration officials to verify dates of arrival for borderline immigration cases. In 2009, a decision was made to destroy those landing cards.[103] The decision to destroy was taken under the last Labour government, but implemented in 2010 under the incoming Conservative government. Whistleblowers and retired immigration officers claimed that they had warned managers in 2010 of the problems this would cause for some immigrants who had no other record of their arrival.[53][103] During the scandal, there was discussion as to whether the destruction of the landing cards had negatively impacted on Windrush immigrants.[10]

The scandal drew attention to other issues relating to UK migration policy and practice, including treatment of other migrants,[104][105][106] and of asylum seekers and what the status of EU nationals living in Britain would be after Brexit.[93][27][67]

Stephen Hale of Refugee Action, said, “All of the things those [Windrush] people have been through are also experiences that people are going through as result of asylum system.[107] Some skilled workers had been threatened with deportation after living and working in the UK for over a decade because of minor irregularities in their tax returns, some were allowed to stay and fight deportation but prevented from working and denied access to the NHS while doing so. Sometimes the irregularities were due to the tax authorities not the migrant.[108]

In an interview with BBC's Andrew Marr on 3 June, Sajid Javid said that key parts of the UK's immigration policy would be reviewed and that changes had already been made to the "hostile environment" approach to illegal immigration in the wake of the Windrush scandal.[109]

Following complaints by ministers, the Home Office is reported to have set up an inquiry to investigate where the leaked documents that led to Rudd's departure came from.[110][111][112]

People born in Jamaica and other Caribbean countries are thought to be more affected than those from other Commonwealth nations, as they were more likely to arrive on their parents' passports without their own ID documents

Having not previously needed documentation they have now found themselves without any way of proving their status today.”

The government did not announce the removal of this clause, nor did it consult on the potential ramifications.

Government measures of reducing illegal immigration undermine credibility in the system due to high instances of inaccuracies and error, an influential group of MPs has warned.

Fees for immigration and nationality applications have steadily risen since 2010 under the “hostile environment” policy … Among the charges are the £3,250 levy for indefinite leave for an adult dependent relative and £1,330 for an adult naturalisation application … The cost to the Home Office of processing a naturalisation application is £372

Fees have risen since 2011, and the cost of registering two children has more than tripled.

shadow foreign secretary Emily Thornberry conceded the phrase "hostile environment" in relation to illegal immigration had first been used under the last Labour government … but it had been cranked up by the Conservatives to a point where "people have died, people have lost their jobs, lost their futures".

Official suspicion about his immigration status led to him being evicted last summer, and he was homeless for three weeks. His disputed status has also led to free healthcare being denied.

Marshall’s case was the first to attract political attention to the Windrush scandal in March.

Aloun Ndombet-Assamba, who served as High Commissioner for Jamaica in London between 2012 and 2016. “We put this on the agenda … in Sri Lanka in 2013.

Downing Street has rejected a formal diplomatic request to discuss the immigration problems being experienced by some Windrush-generation British residents at this week’s meeting of the Commonwealth heads of government, rebuffing a request from representatives of 12 Caribbean countries for a meeting with the prime minister.

The letter informed her “of our intention to remove you from the UK to your country of nationality if you do not depart voluntarily. No further notice will be given” … If she decided to stay, the letter warned, “life in the UK will become increasingly difficult”; O’Brien was liable to be arrested, prosecuted and face a possible six-month prison sentence.

In this system one is guilty before proven innocent rather than the other way around.

Kate Osamor said she wanted the Home Office to explain why a large group of black Caribbean men and women who have been here since the 1960s were being targeted by immigration officials.

Thompson, 63, is not receiving the radiotherapy treatment he needs for prostate cancer because he has been unable to provide officials with sufficient documentary evidence showing that he has lived in the UK continuously since arriving from Jamaica as a teenager in 1973.

Important original documents submitted to the Home Office by applicants are lost, then applications are denied or applicants remain in limbo, sometimes for years because it is claimed documents are not available. Yvette Cooper said, “The Home Affairs committee and the independent inspectorate have warned the Home Office repeatedly to improve the competency and accuracy of the immigration system. It’s crucial they get the basics right. We’ve even recommended digitising and changing the system so people don’t have to submit so many original documents in the first place, given the risk of loss and delay..

Employees in his department told their managers it was a bad idea, because these papers were often the last remaining record of a person’s arrival date.

The Home Office required standards of proof … which went well beyond those required, even by its own guidance … and which would have been very difficult for anyone to meet.

His problems began on 7 May 2012. He was going through Gatwick airport using his new Jamaican passport, as well as his older passport bearing the crucial “indefinite leave to remain” stamp. Instead of letting him keep his old passport, the immigration officer kept it and told him: “You don’t need that, sir.”

Ian Hislop: "This was the Windrush scandal – where a cabinet minister was thrown overboard and the ship of state nearly sank.”

Lammy, calls this a “day of national shame”, telling the Commons: “Let us call it as it is. If you lay down with dogs, you get fleas, and that is what has happened with this far right rhetoric in this country.”

The home secretary said she was not aware of the targets for deportations being used by some officers, when she told a committee of MPs on Wednesday “that’s not how we operate”.

judges were impressed by the tenacity of Amelia Gentleman’s work, her determination to tell the stories of the victims of the government’s hostile environment policy, and the enormous impact her work had.

May has promised to look into the case of a Londoner asked to pay £54,000 for cancer treatment despite having lived in the UK for 44 years, after Jeremy Corbyn raised it at prime minister’s questions.

Both Ms Rudd and Mr Williams said they would “go away and find out”, whether their own department had been setting removal targets, because neither of them were aware.

The Home Office mistakenly detained more than 850 people between 2012 and 2017, some of whom were living in the UK legally, and the government was forced to pay out more than £21m in compensation as a result, officials have revealed

“I don’t know what you’re referring to,” said Amber Rudd, the home secretary, as she was questioned about the existence of targets for removing migrants from the UK.

She told the Home Affairs Select Committee that the Home Office had no targets for removals, then that she was unaware of these targets and that they would be scrapped. Now it emerges that she saw the relevant targets herself.

Harriet Harman: these two people … would have been better off if they'd broken the law and done something wrong. Then the police … would have taken them to court and the state would have had to explain why they were locking them up.

none of the safeguards to prevent against wrongful detention worked. These people were consequently detained unlawfully

This report should alert (the Home Secretary) to the scale of human right violations within the powerful department he now leads.

Theresa May's "hostile environment" policy should change after the "appalling" treatment of the Windrush generation, MPs say

The “appalling treatment” of thousands of Windrush victims shows that the Home Office has become a callous and hostile institution in need of “root and branch reform”.

We are deeply concerned that it took so long for the Government to acknowledge and address the situation of the Windrush generation. Either people at a senior level in the Home Office were aware of the problems being caused but chose to ignore them … or oversight mechanisms failed.

The government has not reached a decision on a compensation scheme more than two months after it was raised by MPs

Staff routinely used landing card information as part of their decision-making process,

The visit to the home of a woman who was in the process of regularising her visa status has raised fresh questions about the fairness and efficiency of Home Office policy.

the Home Office has granted a visa to a woman it had previously classified as an immigration offender, just 24 hours after video footage of a distressing dawn raid on her home was published by the Guardian.

Bowcott, Owen (18 April 2018). "Jamaican PM and Labour MP call for Windrush compensation". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

Access to this requires a premium membership.