The president of Zambia from 1964 to 1991, Kenneth Kaunda, who has died aged 97, stood out as one of the most humane and idealistic African leaders in the post-independence age. A man of great presence and charm, he played a notable role as a leader of the “frontline states” in the long confrontation between independent black Africa and the white-dominated south of the continent, which came to an end only in 1994 with the election of Nelson Mandela as president of South Africa.

He was a consummate politician and spent much of his time shuffling his top party figures around in a chess game to balance ethnic groups and their claims to power-sharing; he also possessed a ruthless streak which he deployed towards opponents, although his abhorrence of violence was a rarity in that era.

One of Africa’s longest-ruling heads of state, he, like so many other politicians, did not know when to quit. However, when finally he was defeated at the polls, he stood down with grace.

An idealist and visionary, he lacked intellectual rigour and his attempt at political philosophising represented a mish-mash of ideas that were only a pale imitation of the thinking of his friend and neighbour in Tanzania, President Julius Nyerere. An emotional man who often wept in public, Kaunda liked singing hymns and folk songs, and was a Christian inclined to mysticism.

His lack of flair for economics proved his nemesis. At independence in 1964, copper was booming and it provided Zambians with a relatively high standard of living, but when the boom came to an end in 1973, Kaunda showed little capacity to deal with the country’s new problems and Zambia instead became increasingly indebted. Economic conditions deteriorated, and though the decline was not all Zambia’s fault, Kaunda was too busy on the international stage and promoting “confrontation” with the south. His critics, who multiplied during his last decade in office, said that had he devoted as much attention to Zambia’s own problems, it would not have descended to the level of poverty it reached by the end of the 1980s.

Had he resigned in 1980 he would have gone with his reputation high. Instead, he clung on too long, and though he won his first six elections (mainly under a one-party system) without a rival to challenge him, he became increasingly remote even from his own party’s stalwarts.

He was born at Lubwa near Chinsali in the northern province of Northern Rhodesia, as Zambia was then called; his parents were immigrants from Nyasaland (as Malawi was then). His father, David, was a priest who became a teacher and his mother, Helen, was one of the first black teachers in the colony. They had been married for 20 years, and had seven children already, and he was christened Buchizya, “the unexpected one”. He was educated at Lubwa Church of Scotland mission school and then at Munali school, Lusaka – the premier secondary school for Africans in Northern Rhodesia. In 1943 he began teaching at Lubwa mission; he then spent time in Tanganyika, as Tanzania was then, before returning to become head of his old school in 1947.

Kaunda now became involved in politics, first as secretary of the local young men’s farming association, which was a stepping stone to the Northern Rhodesian African National Congress (a separate organisation from the South African ANC, but with similar objectives of independence). In 1948 he founded and became secretary general of the Lubwa ANC branch; in 1950 he was appointed organising secretary of the ANC nationally. He showed energy and administrative capacity in this role, and soon rose to become secretary general of the ANC and deputy to its leader, Harry Nkumbula.

He found himself having increasing brushes with the colonial authorities. He was firmly opposed to the Central African Federation (CAF), which came into being in 1953 as an attempt by Britain to unite the three territories of Northern and Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland in what would have become a white-dominated dominion.

In 1955 he was jailed for possessing banned literature and while in prison vowed to give up smoking and drinking, a vow he was to keep all his life. Widening his political horizons, he visited Britain for the first time in 1957 and then went on a trip to India, where he was seriously ill with tuberculosis.

On his return to Northern Rhodesia, Kaunda found a disheartened ANC that was suffering from the faltering leadership of Nkumbula, who was seen not to be tough enough in standing up to white interests; in October 1958 Kaunda, with a number of other young radicals, left the ANC to form the Zambia African National Congress (ZANC) with himself as president.

A formative experience for him was a visit he made to Ghana in December 1958 to attend the first All African People’s Conference, which had been called by the newly independent country’s prime minister, Kwame Nkrumah. There, Kaunda had the opportunity to meet many of the continent’s leading nationalists. On his return to Northern Rhodesia he continued to oppose the limited constitutional arrangements then coming from the Colonial Office and ordered the ZANC to oppose them. In March 1959 he was arrested for holding an illegal meeting – by then he was seen as the main opponent of the CAF in the colony – and was sentenced to nine months in prison. While in prison he suffered a second serious bout of TB.

In January 1960, after his release, he formed a new party, the United National Independence party (UNIP). His aim now was to take Northern Rhodesia out of the CAF and achieve immediate independence, and he launched a massive campaign of civil disobedience. Initially, he opposed the 1962 constitution, written by the British to accommodate both white settlers and native Africans, which he did not think went far enough, but when Nkumbula and the ANC decided to contest the elections that October, he changed his mind and contested them as well. The result was inconclusive and UNIP joined with the ANC to form the colony’s first government with an African majority, in which Kaunda became minister of local government and social welfare. The CAF came to an end at midnight on 31 December 1963, and a new constitution for Northern Rhodesia provided for self-government.

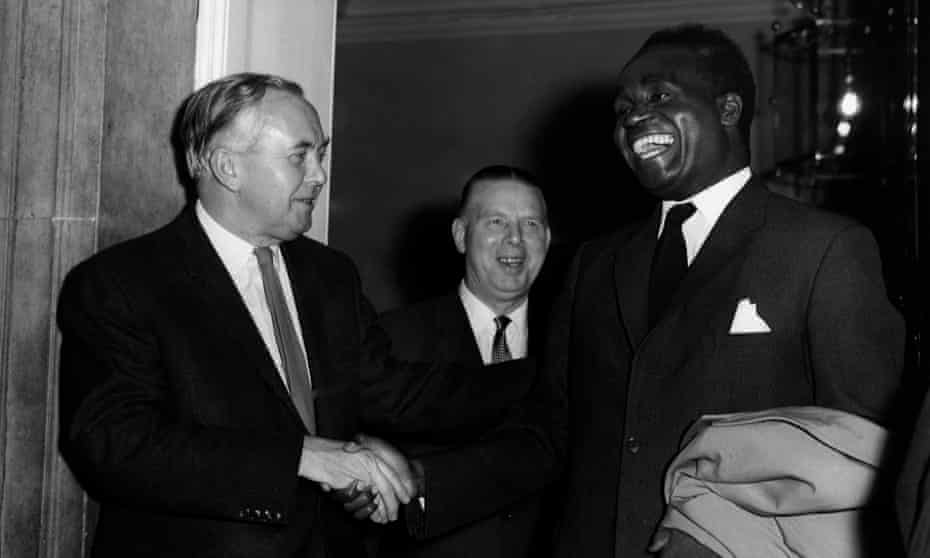

During January 1964 Kaunda led UNIP in a brilliant electoral campaign to obtain a landslide victory and he became prime minister of Northern Rhodesia, the youngest in the Commonwealth. He attended independence talks in London the following May and on 24 October Northern Rhodesia became independent as Zambia with Kaunda as its first president, at the height of his popularity and prestige.

However, events to Zambia’s south were already building up to a crisis. Nationalist wars against the Portuguese had begun in Angola (1961) and Mozambique (1964) and were to turn into civil wars when the Portuguese withdrew in 1975. In Southern Rhodesia, the end of the CAF was merely the prelude to the unilateral declaration of independence (UDI) in November 1965 by the white-minority government of Ian Smith, while in South Africa Hendrik Verwoerd, the high-priest of apartheid, was busy entrenching the system while also controlling Zambia’s neighbour South West Africa (Namibia).

Once UDI had been declared in Rhodesia, Kaunda declared a state of emergency in Zambia. He was to make many pleas to Britain to intervene in Rhodesia, but they fell on deaf ears. At home, meanwhile, he became involved in a permanent balancing act between different ethnic power groups. He was re-elected in 1968, still the country’s most charismatic political figure, and despite the adverse effects of UDI the price of copper remained high through the 1960s, keeping economic prosperity at a reasonable level.

But Zambia was beginning to suffer as a result of its landlocked position, especially as copper was both bulky and heavy and had to be transported along the Benguela railway through Angola, which would later be cut as a result of war, or along the railways to the south with outlets in Mozambique. The country was increasingly at the mercy of its neighbours and constantly obliged to compromise to ensure the copper got out. (The Chinese-built Tanzania-Zambia railway from Dar-es-Salaam to Kapiri Mposhi was not completed until 1976 and soon ran into technical difficulties.)

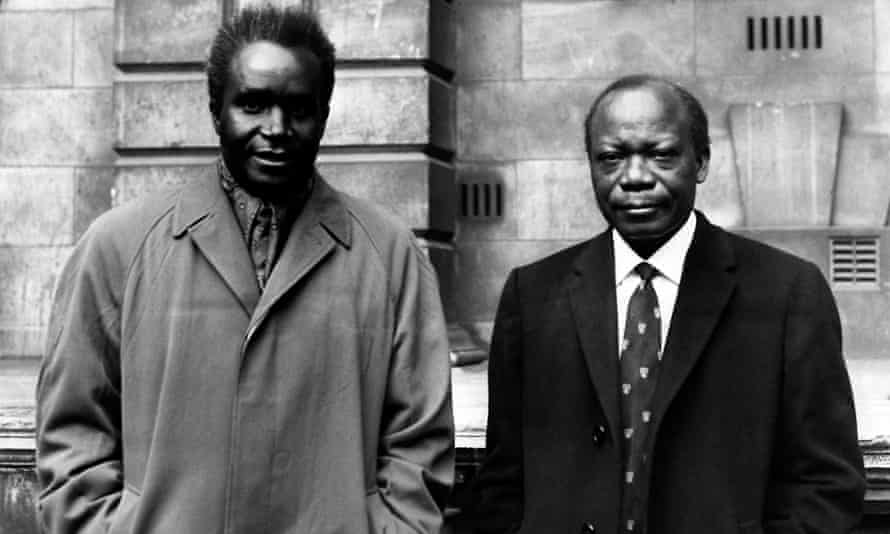

At the beginning of the 70s Kaunda fell out with his old friend and then vice-president, Simon Kapwepwe, the most able of his supporters from the independence struggle. Kapwepwe was finding Kaunda’s increasingly autocratic style hard to take, so he broke with UNIP and formed his own party, the United Progressive party (UPP). Kaunda’s reaction was to imprison him and, in 1972, make Zambia a one-party state. After Kapwepwe’s release from prison, he eventually rejoined UNIP but the old closeness had gone. In 1973, now as sole candidate, Kaunda won a third presidential term.

A turning point in the fortunes of both Zambia and Kaunda came with the fall in copper prices in 1973: it was the beginning of what turned into a permanent economic crisis. Borrowing developed into a habit, until, on a per-capita basis, Zambians were among the most indebted people in the world.

Kaunda blamed events to the south for Zambia’s problems, but after 1980, when Rhodesia became independent as Zimbabwe, this was an increasingly hollow excuse. A failed coup in 1980 emphasised his growing unpopularity.

The following decade witnessed steadily deteriorating living standards for ordinary Zambians. Kaunda tried austerity measures, including cutting food subsidies, but this led to three days of rioting and 29 deaths; he turned to the IMF but then, in May 1987, rejected its remedies, while foreign creditors refused further support.

In 1974 he had attempted a dialogue with South Africa’s prime minister, John Vorster, that had come to nothing, but though other African leaders criticised him for it, his efforts to find solutions in southern Africa were rewarded in 1979 when Zambia’s capital, Lusaka, was made the venue for the Commonwealth heads of government meeting of that year : it also became the headquarters for the ANC and Swapo, the South West Africa People’s Organisation. Kaunda succeeded Nyerere as chairman of the frontline states and, in 1987, he also became chair of the OAU, the Organisation of African Unity.

Kaunda’s reputation outside Zambia stood much higher than at home. Despite his external activities, by 1990 his popularity had sunk to an all-time low. There was another attempted coup, which was easily put down, though many clearly had hoped it would succeed. Demands for pluralism were now coming from both Zambia’s national assembly and his party, and by the end of the year the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD) was holding rallies nationwide to demand change. In December 1990, Kaunda signed a bill to transform Zambia into a multi-party state, though included in it were increased powers for the president, which angered his opponents.

Finally, after meeting members of the opposition for the first time, Kaunda agreed a more acceptable constitution in June 1991. The following month, when he attended a football match in Lusaka, he was pelted with oranges and beer tins. Elections were held in October 1991 and resulted in a huge defeat for UNIP, which held only 25 seats to 125 for the new MMD. In the November presidential elections the trade unionist Frederick Chiluba obtained three times the number of votes cast for the incumbent.

Kaunda was the first African president to be defeated at the polls and retire gracefully. To Chiluba, he said: “My brother, you have won convincingly and I accept the people’s decision.”

The new government hardly responded in like fashion, and it was more than two years before it gave him the pension to which he was entitled. In 1992 he announced he was leaving politics and stepped down from the leadership of UNIP; instead, he wished to create a foundation to work for peace, democracy and African development. By 1994, however, he had tried a comeback that did his reputation no good, yet such was his charisma that Chiluba resorted to a widely condemned change to the constitution in May 1996 which required presidential candidates to be second-generation Zambians (Kaunda’s parents had come from Nyasaland). This would later prevent the 2014-15 acting president, Guy Scott, whose parents were British, from being a candidate.

In August 1997, Kaunda attended a UNIP political meeting at Kabwe; this was broken up by the police who fired upon him, wounding him slightly in the head. He was detained after a failed coup against Chiluba that October, but denied involvement and charges against him were withdrawn.

Kaunda was always closely supported by his wife, Betty (nee Banda), whom he married in 1946. She died in 2012. They had nine children, one of whom, a son, Wezi, was shot dead in 1999 in what appeared to be a random carjacking, but the Kaunda family believed to be a political assassination. Another died of HIV/Aids in 1987; in retirement, Kaunda worked for organisations combating the spread of the illness.

Kenneth David Kaunda, politician, born 28 April 1924; died 17 June 2021

Guy Arnold died in January 2020