Review of thousands of legal actions show that Trump is fiercely protective of his brand, quick to distance himself from deals that struggle, willing to deploy outsized resources against adversaries and sometimes prone to micro-management, even in disputes that involve relatively small amounts of money. Those approaches, however appropriate in a business setting, may not translate to a political one, especially at the level of the White House.

Among the details:

• Trump distances himself from deals that sour.

When projects struggle, Trump doesn’t hesitate to cut ties, even those that relied on his name to secure investments. That was the case in condo projects that were never completed in Fort Lauderdale, Tampa, Panama and Baja, Mexico.

Condo buyers who sued to get their deposits back often said they believed Trump was a full partner in the buildings. Trump was shielded by disclaimers in sales agreements explaining his branding-only role, though plaintiffs and their lawyers argued in court that fine print didn’t sync with marketing materials that made it appear these were Trump properties.

In depositions and court filings in the condo cases and similar branding deals, Trump's team appears to try to have it both ways in depicting his involvement. On one hand, Trump contends deep influence over even the smallest details to ensure Trump-branded products and developments are up to his standard, and he places high importance on the influence of his marketing muscle in such deals — usually as the lead name, face and voice behind a project.

On the other hand, his team argues in court that he's not liable for the deals that fail because he's simply lent his name.

Trump himself walked lawyers through the difference between a brander and a developer in a 2013 deposition in one of the Fort Lauderdale condo cases.

“Well, the word ‘developing,’ it doesn't mean that we're the developers,” Trump said, arguing he’s not accountable when a project he lends just his name to goes under. “We worked on the documents, we worked on the room sizes and the things, but we didn't give out the contracts, we didn't get the financing, we weren't the developer, but we did work with the developer.”

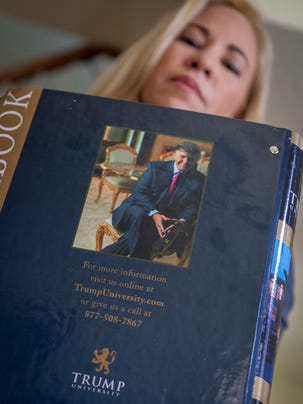

Sherri Simpson holds up a book of class materials she received when she started the Trump University program on real estate investing.

(Photo: Kelly Jordan, USA TODAY)

In lawsuits over his Trump University, he testified that he had never met instructors who were described in the university’s promotional materials as being “handpicked” by him. “It depends on the definition of what that means, handpicked,” Trump said during an exchange with a lawyer in a sworn deposition last December.

When attorneys representing plaintiffs pointed out some instructors had criminal pasts and had been accused of berating seniors who signed up for the program, Trump replied: “In every business, people slip through the cracks.”

Florida attorney Sherri Simpson, who defends homeowners in foreclosure actions, said she signed up for Trump University classes because she hoped to capitalize on low prices during the housing downturn. She wanted to turn to a trusted real-estate name to learn how.

“I’m aggravated that I lost all that money,” she said in an interview. “He promised to hire the best, to handpick the instructors, make sure everyone affiliated with the program was the best. But he didn’t do that.”

• Trump is willing to spend large sums on small claims.

No detail is too small for a Trump suit, and he often brings to bear overwhelming legal resources that enable him to outlast his adversaries.

In February, he filed five lawsuits against eight neighbors of his Doral golf club in Miami for $15,000 in damages to reimburse him for "vandalizing" or "destroying" expensive areca palms and other plants his groundskeepers installed between their homes and the course. Trump's staff says the foliage was planted to block golfers' views of the houses; the homeowners say the trees blocked their views of the course. All five cases are pen

A view of the entrance sign at Trump National Doral luxury resort in Miami, Fla. -- (Photo: Kelly Jordan, USA TODAY)

“No other developer put so many resources in trying to fight claims brought by the plaintiffs,” said Jared Beck, a Miami attorney who has represented dozens of clients in lawsuits against developers in South Florida. He said none has fought with the tenacity of Trump, citing a “mismatch of resources” that often works in Trump’s favor.

Beck is now appealing to the Florida Supreme Court a case that dates to 2008 in which he represented a group of people who invested in condos in a failed development in Fort Lauderdale to which Trump licensed his name. “He is willing to go to the mat and has practically unlimited resources.”

• Trump fiercely protects the monetary value of “Trump” as a brand name.

Trump publicly has placed the value of his licensed real estate and other branding deals at $3.3 billion, though Forbes and other analysts question whether the figure is inflated. His moniker drives the value of his licensing deals, which now make up an important arm of his business model.

In one case, a South Florida developer hired experts who testified that having Trump's name attached to their proposed condominium development boosted the condos' value by at least $200 per square foot. The swanky seaside complex was only partially built, prompting some condo buyers to file a lawsuit against Trump and the developers seeking to recover their deposits. The developers had paid to license Trump’s brand, allowing them to use Trump’s name, his image and his reputation to help them sell units.

This condo building in Fort Lauderdale failed to develop as a Trump project. Buyers lost their deposits after the real estate crash and sued Trump for what they say was fraudulent marketing materials. Trump himself was deposed in the suit and explained the inner workings of his licensing agreements that shielded him from the litigation. -- (Photo: Kelly Jordan, USA TODAY)

Trump has attempted to pull out or distance himself from similar licensing deals, real estate and otherwise, if he feels the situation is hurting his brand. He also goes to court to collect royalties and other fees he says he's owed on those same kinds of deals.

“Anything I put my name to is very important,” Trump said in a 2010 deposition tied to a failed real-estate development in Tampa licensed to carry Trump’s “mark," as he calls it. "If I allow my name to be used, whether it’s a partnership or whether it is a licensing deal, they are all very important to me.”

Trump sued for $4.5 million over unpaid royalties after a company that had been paying him to call its liquor Trump Vodka fell on hard times during the economic downturn, hurting sales of pricier spirits. The company stopped making its licensing payments, and Trump terminated the deal and sued to recoup what he was owed. He won a judgment for the amount, though it's unclear whether he ever collected from the troubled company.

And he has been aggressive in suing unrelated companies that were using his name without permission. He won rulings over attempts to market Trump’s Best Coffee, a series of websites with names like trumpabudhabi.com and trumpbeijing.com, and a marketing agency calling itself Trump Your Competition.